The Essentials:

From vibes to metrics: The new ‘Belém Package’ creates a precise ruler for the world's fragility, codifying 59 voluntary indicators to turn the nebulous concept of resilience into hard, audit-ready data.

The funding chasm persists: While the diplomatic toolkit has expanded, the financial commitment has not; the pledge to triple adaptation finance to $120 billion by 2035 leaves a massive $245bn annual shortfall against actual needs.

A compliance trap for the vulnerable: The new framework risks becoming an unfunded mandate, forcing poorer nations to divert scarce resources toward expensive consultants rather than actual infrastructure.

Metrics are not a market cure: While standardisation aims to attract private capital by reducing uncertainty, adaptation will often remain a stubborn public good—better measurement doesn’t inherently turn a sea wall into a revenue-generating asset.

Money vs. Metrics

To the modern diplomat, a problem measured is a problem halved. To the resident of a sinking Pacific atoll, however, a problem measured is merely a problem documented.

This dissonance was on full display in Belém last weekend as the curtain fell on COP30. In the somewhat air-conditioned negotiation halls, delegates largely celebrated the ‘Belém Package’ as a triumph of technocratic will. For the first time, the world has agreed on a Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) that is not merely a vibe, but a spreadsheet. Fifty-nine voluntary indicators have been codified to track humanity’s resilience to a warming planet.

It is a victory for the accountants. The world now possesses a precise ruler to measure its own fragility. Yet outside the conference centre, the mood was less jubilant. While the diplomats were busy calibrating their yardsticks, the financiers were busy tightening their purse strings. The summit’s headline pledge—to triple adaptation finance to $120 billion by 2035—was greeted with the polite applause usually reserved for a distant relative’s wedding toast: well-intentioned, but fundamentally inadequate.

The result is a distinct paradox. The international community has built a high-fidelity surveillance system for a collapsing building, while declining to pay for the structural engineers.

The Tyranny of the Dashboard

Give the mandarins their due: the Belém indicators are a feat of diplomatic engineering. Since the Paris Agreement in 2015, adaptation has been the poor relation of mitigation. Decarbonisation is easy to count (tonnes of CO2 are fungible); resilience is not. How does one compare a sea wall in Bangladesh with a drought-resistant crop in Ghana?

The new framework attempts exactly this. It introduces metrics for water security, health, and infrastructure that promise to turn the nebulous concept of ‘resilience’ into hard data. For the donor class in London and California, this is catnip. It promises a future where aid efficiency can be plotted on a scatter graph, and where impact is audited rather than assumed.

But data is not a free good. It is an industrial product. Implementing these 59 indicators requires technology and technical know-how. For a wealthy nation, this is an administrative upgrade. For a Least Developed Country (LDC), it is an unfunded mandate. There is a grim irony in asking the world’s poorest civil services, already straining under the weight of debt and disaster, to divert their scarce resources into filling out ever-more complex forms about their own destitution.

A Fiscal Rounding Error

If the metrics track was a qualified success, the finance track was a study in cognitive dissonance. The headline figure—$120 billion in adaptation finance by 2035—is technically a tripling of the 2025 goal. In the press room, this allowed for a narrative of momentum.

In the real economy, however, it is a rounding error.

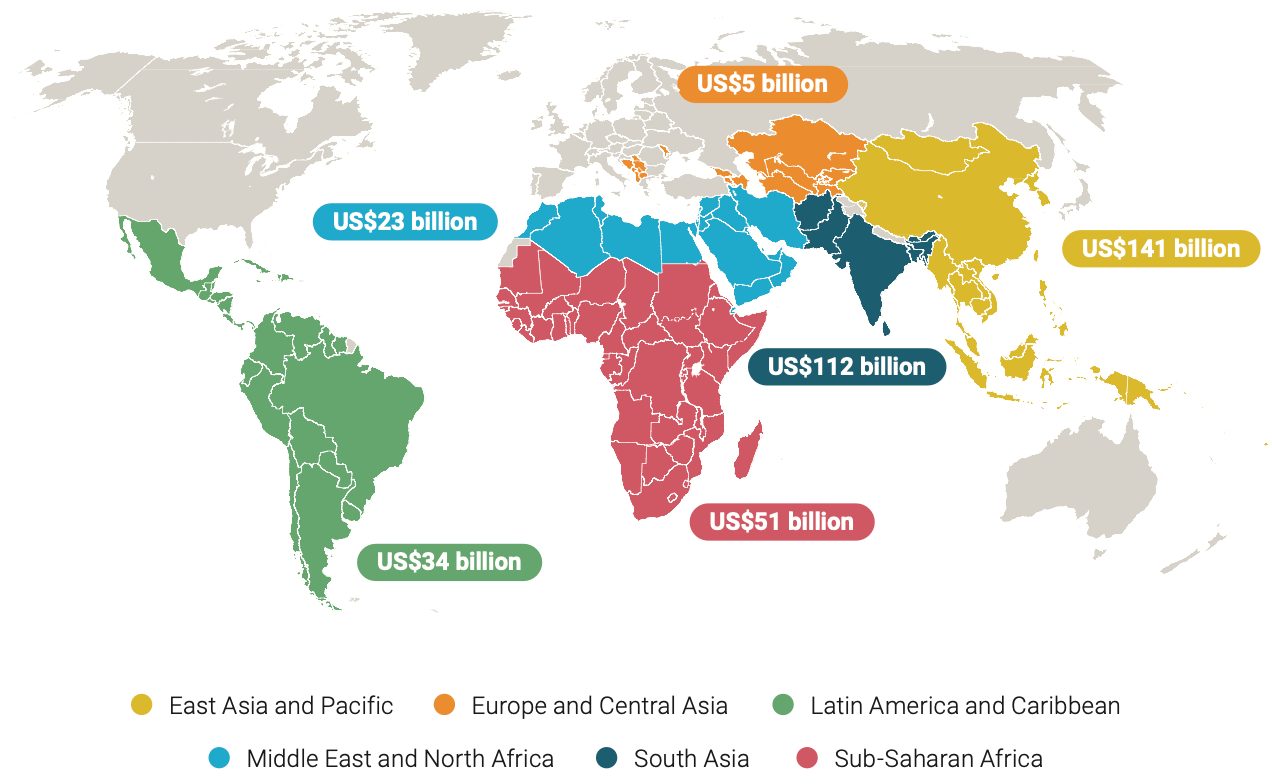

Consult the latest Adaptation Gap Report from the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), published just before the summit. It estimates that by 2035, the annual financing needs of developing countries for adaptation will stand at approximately $365 billion.

Do the maths. Even if the donors hit their $120 billion target—a heroic assumption given their history of missed deadlines—it leaves an annual shortfall of $245 billion. The tripling goal, therefore, is like offering a man dying of thirst a thimble of water instead of a drop, and expecting gratitude for the 300% increase.

This gap is not merely a deficit; it is a chasm. And it turns the new GGA indicators from a tool of management into a tool of despair. We are effectively asking nations to meticulously document a funding gap that we have already decided not to close.

The Compliance Trap

Consider the plight of a hypothetical bureaucrat in Nepal’s Ministry of Forests and Environment. Under the new Belém regime, they are encouraged to report on the stability of glacial lakes (Indicator Category: Water & Ecosystems). To do so requires high-altitude monitoring stations and real-time telemetry.

Yet the funds to buy this equipment are nowhere to be found. The Baku Adaptation Roadmap, the procedural sidecar to the main agreement, promises to look into the "means of implementation" as a work program for 2026-2028. In UN-speak, this is the equivalent of ‘the cheque is in the post’.

Meanwhile, the perverse incentives of development finance kick in. To access the trickle of funds which are available ($120 billion divided by 150 developing nations is thin gruel indeed), our Nepali bureaucrat must prove his project aligns with the new global metrics. They must hire consultants pouring money into reports on ‘Indicator 4.2: Transport Resilience’, diverting cash that might have otherwise poured into concrete for an upgraded bridge.

This is the compliance trap. The Global North, having failed to cut emissions sufficiently to prevent the crisis, is now imposing a heavy administrative tax on the victims, demanding they quantify their suffering in a format that fits a Brussels spreadsheet. It smells faintly of what critics call ‘soft colonialism’—control exerted not through guns, but through grant conditions.

Measuring the Misery

There is a logic to the madness, of course. Private capital, the holy grail of climate finance, loathes uncertainty. The theory goes that if adaptation can be standardised—turned into an investable asset class with clear ROI—the pension funds and asset managers will finally open the floodgates.

Perhaps. But adaptation is stubbornly public. There is no revenue stream from a seawall that protects a fishing village. No amount of clever metrication will turn a flood defence in Mozambique into a venture capital unicorn.

The Belém Package has given the world a dashboard. That is better than flying blind. But a speedometer does not fix an engine, and a thermometer does not cure a fever. By fixating on the measurement of resilience while starving the funding of it, COP30 risks creating a Potemkin village of climate action: a beautifully detailed façade with nothing behind it.

As delegates fly home, leaving the humidity of the Amazon for the winter chill of the northern hemisphere, they leave behind a world that is now perfectly equipped to measure exactly how unliveable it is becoming. It is a triumph of accounting. It remains to be seen if it is a triumph of survival.

Know someone interested in adapting to a warmer world? Share Liveable with someone who should be in the know.

Or copy and paste this link to share with others: https://research.liveable.world/subscribe