The Essentials:

From Planning to Pavement: The global adaptation landscape has reached a decisive turning point, shifting from conceptualisation to implementation.

The Blueprint for Survival: 144 countries have initiated the National Adaptation Plan process, with 68 developing nations submitting Plans to the UNFCCC.

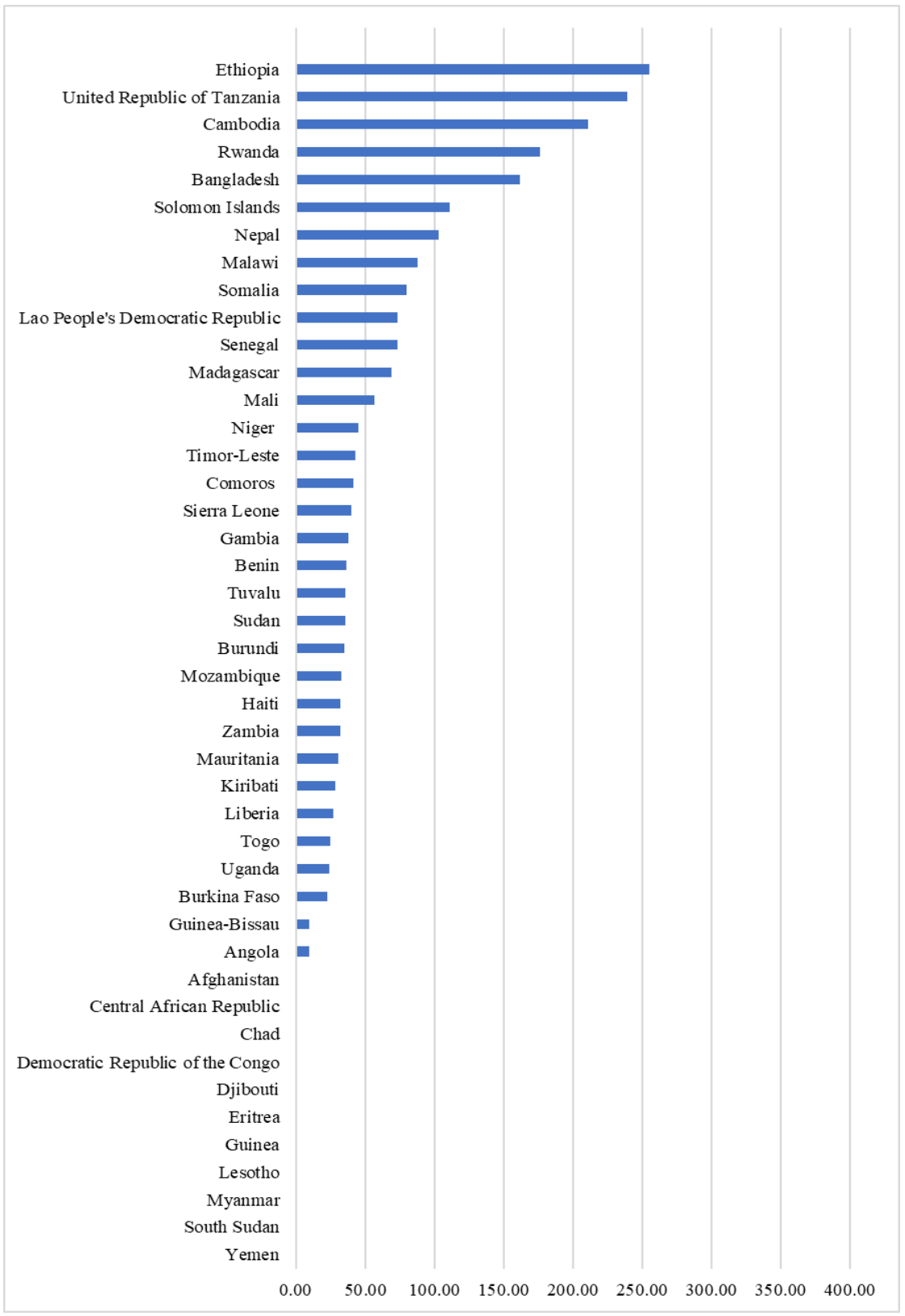

A Trillion-Dollar Requirement: The financial ambition of these plans is immense; requirements range from Ethiopia's $90 billion to Bangladesh's $230 billion, yet current implementation remains constrained by resource gaps.

Countries like Uruguay and Senegal are bridging the implementation gap by developing specialised sectoral NAPs and solutions that translate high-level national goals into investable infrastructure and local development pipelines.

Shifting from PDFs to Protection

The 2025 National Adaptation Plan (NAP) Expo in Lusaka was not merely a meeting of bureaucrats; it was the site of a declaration of a "decisive shift" in the adaptation landscape. For over a decade, the process of formulating National Adaptation Plans was largely a conceptual exercise—an era of mapping hazards and drafting PDFs. But as of late 2025, the world has reached a pivot point. The era of the ‘Paper Plan’ is ending, and the era of doing has begun.

Across the developing world, 144 countries have now launched their NAP processes, with 68 having submitted full, strategic roadmaps to the UNFCCC. These documents have become sophisticated defence manuals, identifying 63 specific hazards—led by droughts and floods—and outlining how to survive them. Yet, as these plans move from the secretariat’s desk to the muddy reality of implementation, a massive implementation gap has been exposed. The foundations are being laid, but the transition to fully financed, resilient infrastructure remains a work in progress.

The Paper Wall: A Trillion-Dollar Stumbling Block

The central tension of the NAP process is the yawning chasm between a country’s ambition and its bank account. The Green Climate Fund (GCF) has been a crucial engine, approving $6.91 billion for 116 adaptation projects across 58 countries. On any other scale, $7 billion would be a triumph. In the context of climate adaptation, it is a rounding error.

Consider the sheer scale of the requirements documented in the 2025 reports. Bangladesh estimates its adaptation needs at a staggering $230 billion between now and 2050. Ethiopia, facing systemic risks to its agriculture, requires $90 billion. Nepal’s bill sits at $47.4 billion. When compared to the current trickle of international public finance, the math does not add up. Implementation is currently described as "fragmented" and "insufficient" relative to the escalating risks. Accessing the available funds remains a marathon of "complex procedures" and "persistent challenges”, particularly for Least Developed Countries (LDCs) that lack the institutional capacity to manage massive, direct-access grants.

Financial Innovation: The Bhutanese Safety Net

In this climate of scarcity, the most successful countries are those treating adaptation as a laboratory for financial innovation. Bhutan provides a valuable case study in this approach. Rather than waiting for a single, multi-billion-dollar dike project, Bhutan has moved to protect its most vulnerable citizens through index-based microinsurance.

By scaling up insurance that is automatically triggered by weather data, Bhutan is building a financial cushion for smallholder farmers. It is a model that bypasses traditional bureaucratic delays, ensuring that a climate shock does not become a permanent slide into poverty. Furthermore, Bhutan is documenting and integrating traditional and Indigenous knowledge systems into its conservation efforts, ensuring that innovation in insurance is supported by centuries of local environmental wisdom.

Beyond insurance, the most resilient nations are integrating adaptation directly into their social safety nets. In Haiti, the GCF-financed Trois-Rivières project combines flood management with a short-term social protection system that provides food coupons to nearly 1,000 households impacted by climate events.

In Ethiopia and Mozambique, adaptation is being linked to social protection through decentralised planning, ensuring that employment creation and food security measures are climate-proofed. These initiatives prove that adaptation is not just about engineering; it is about "adaptive social protection” that prevents the poorest from falling through the cracks when the rains fail or the rivers rise.

The Sectoral Breakdown: Uruguay’s Comprehensive Strategy

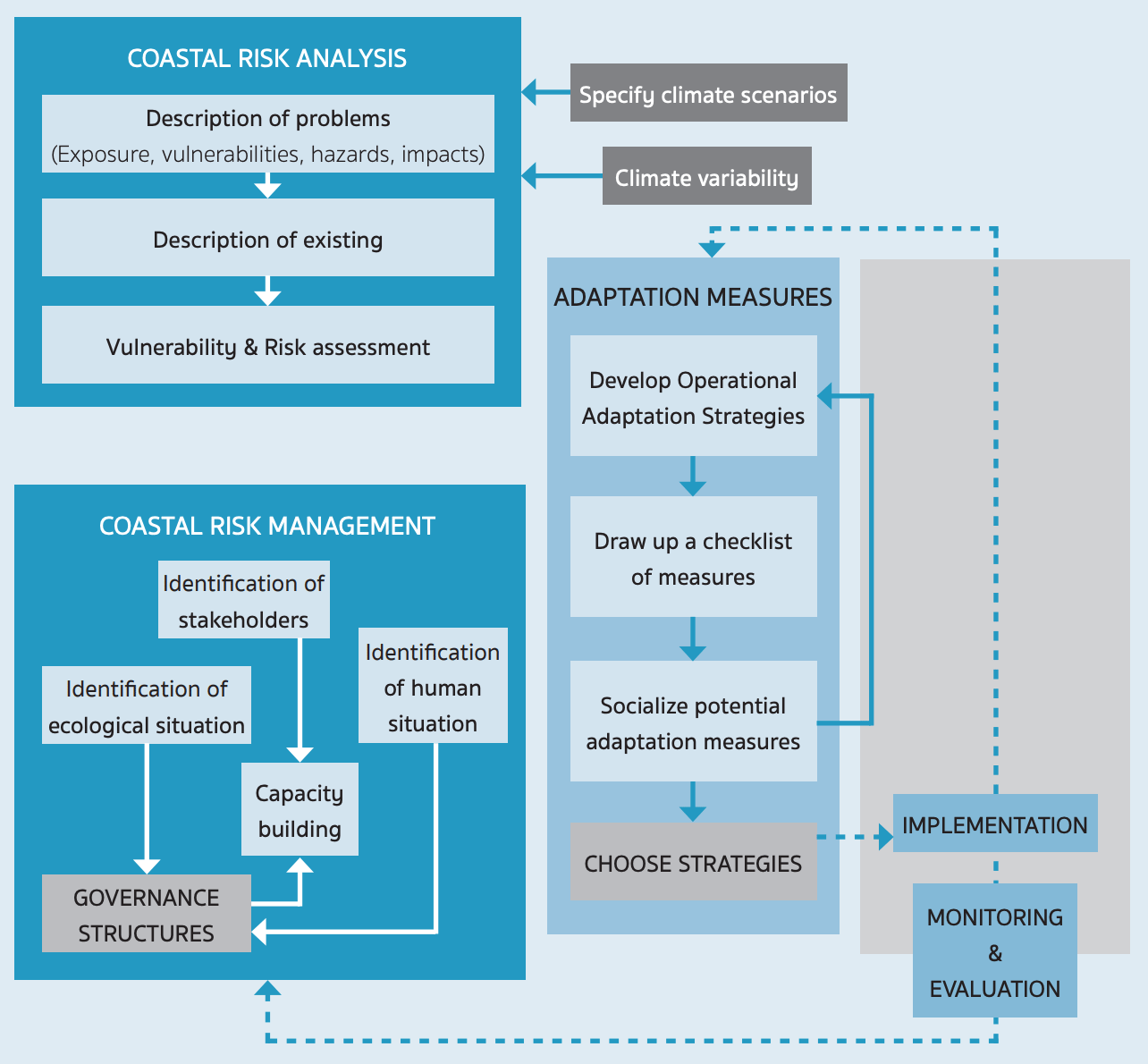

While many nations produce broad, high-level summaries, the gold standard of NAPs favours precision. Uruguay has distinguished itself by submitting not just a national plan, but a suite of sectoral NAPs targeting specific vulnerabilities: Cities and Infrastructure, Agriculture, Energy, and Coastal Zones.

By breaking down the problem, Uruguay has been able to align climate risk assessments with investment planning and engage the private sector more effectively. Senegal has followed a similar path, focusing its efforts on agriculture and coastal sectors to implement nature-based solutions that restore ecosystems while protecting livelihoods. The lesson is clear: general plans win headlines, but sectoral plans win funding. When adaptation is translated into the specific language of a city’s zoning laws or a country’s energy grid, it becomes investable.

The Last Mile Challenge

The most sophisticated risk assessment is worthless if it cannot reach the person standing in the path of a storm. The 2025 report highlights a significant advance: 119 countries now have multi-hazard early warning systems in place, more than double the number in 2015.

However, significant challenges remain in disseminating these warnings to ‘last-mile communities’. In many LDCs, digital connectivity is hampered by high mobile internet costs and poor network coverage. In these regions, the laboratory must go low-tech: radio and television remain vital lifelines. Success in countries like Cambodia and Togo has relied on participatory approaches and multi-sectoral coordination to ensure that warnings are not just issued, but understood and acted upon by local communities.

Conclusion: The 2025 Pivot

As 2025 draws to a close, the global adaptation landscape has shifted from a "conceptualisation and planning" phase to one of "consolidation and implementation". The “analytical and institutional frameworks”—the hardest and most technically demanding part of the process—are largely complete. By the end of 2025, most developing countries will have submitted their first NAPs or be on the cusp of doing so.

The deadline has become a lifeline. The transition now requires a "decisive shift" in finance to move beyond fragmented, project-based support toward sustained, programmatic funding. The NAP formulation process has shown that adaptation works best when it is local, legal, and linked to the economy. In a world of escalating risks, the only true failure is a plan that stays on the page. For the 68 nations that have submitted their NAPs, the blueprint for survival is ready; it is time for the pavement to meet the plan.

Know someone interested in adapting to a warmer world? Share Liveable with someone who should be in the know.

Or copy and paste this link to share with others: https://research.liveable.world/subscribe

Social Protection as a Shield