The Essentials:

The disclosure-action chasm is real: 80% of companies acknowledge physical climate risks, yet fewer than 1% allocate capital to adaptation—creating a mammoth funding gap by their own risk assessments.

Capital exists, incentives don't: Fortune 500 companies accrue $41.7 trillion in annual revenue, and adaptation investments generate $7-10 in returns for every $1 deployed, yet boardrooms remain structurally misaligned.

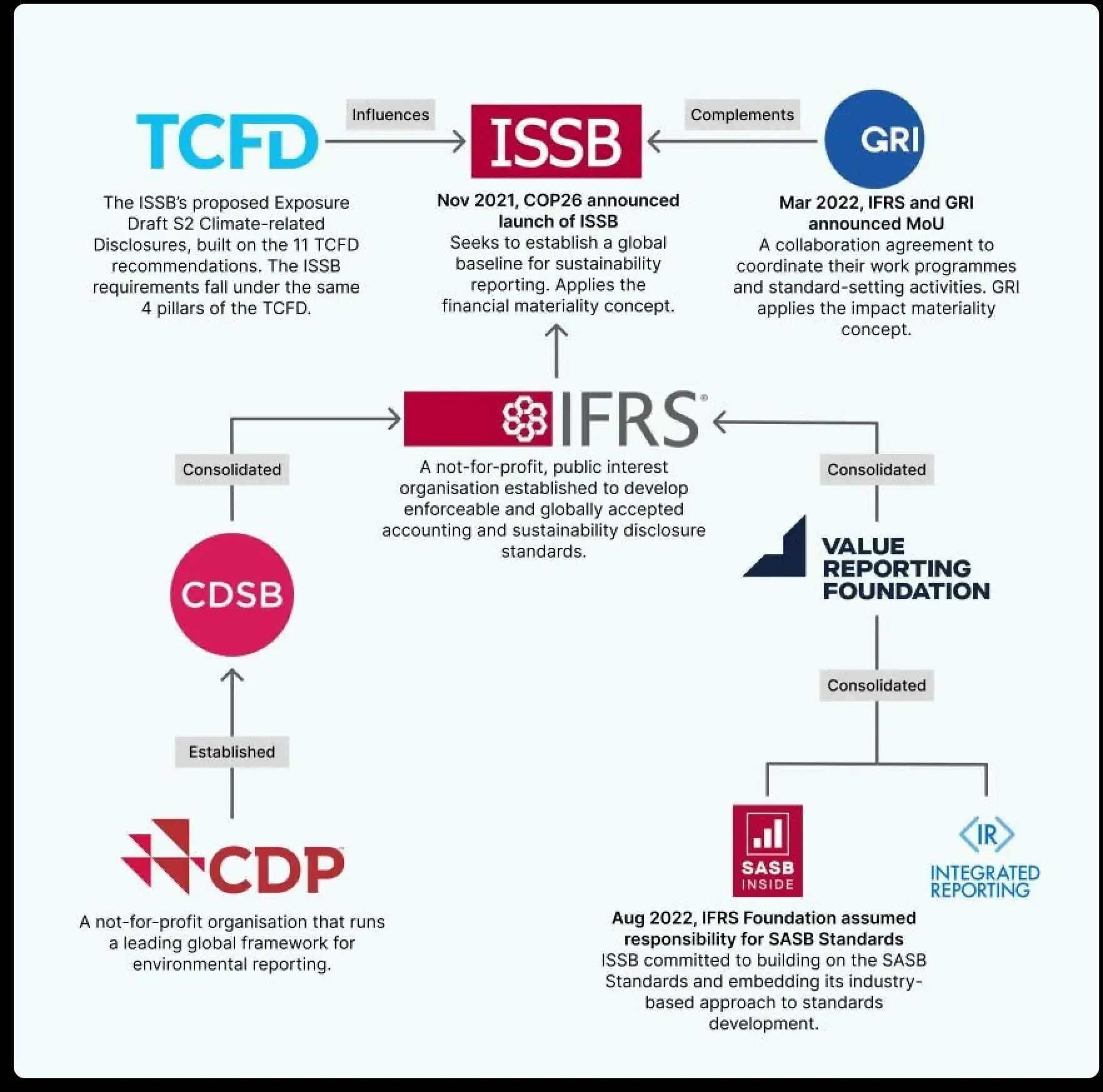

Repricing with incoming regulations: Regulatory mandates (CSRD, ISSB) will force adaptation spending into public view; insurance withdrawal and market repricing will turn inaction into a significant valuation discount for laggards.

Disclosure as a Substitute for Action

80% of the world's 2,300 largest companies have made a startling admission: physical climate risks—floods, droughts, hurricanes, wildfires—pose material threats to their business. Nearly half have drafted emergency response plans. Yet fewer than one in a hundred has actually allocated capital to manage these risks. This is not a disclosure problem. It is an implementation problem. And as investors, regulators, and nature itself grow impatient, the consequences of this gap are becoming impossible to ignore.

Bloomberg’s analysis reveals a chasm so vast it now characterises the central breakdown in how corporations manage climate risk. Companies have mastered the ritual of reporting—investors expect it, regulators demand it, and marketing departments know how to spin it. But somewhere between identifying a risk and funding its mitigation, something goes catastrophically wrong. The talk-walk hypothesis, long suspected by researchers, is now quantifiable. And the price of ignoring it is rising.

The Reporting Parade Exposing the Charade

Of 2,300 global corporations analysed by Bloomberg, only 0.61% report any adaptation capital expenditure, and just 0.57% disclose spending aligned with EU taxonomy standards. Adaptation remains an afterthought in corporate boardrooms despite mounting exposure: physical climate impacts cost the global economy at least $1.4 trillion in 2024 alone. The gap widens when examined through corporate budgets. Private-sector adaptation finance reached only $5 billion in 2025, up from $1.5 billion in 2019—a tripling that still pales against company exposure.

This is not a capital availability problem. Fortune 500 companies collectively generated $41.7 trillion in revenue in 2024. The Global Center on Adaptation estimates that $1.8 trillion invested in adaptation from 2020 to 2030 could generate $7.1 trillion in net benefits—returns that rival renewable energy investments. Yet capital does not flow toward resilience. Why? Adaptation lacks standardised metrics, data on investment returns, and global scalability. A solar farm is broadly replicable across borders, and its financial returns can be measured; a flood barrier solves a localised problem. Localised solutions are typically not scalable, nor easily measurable. Scaleability and measurability are what capital markets reward.

The structural misalignment is clear: the person measuring climate risk controls no capital budget; boardrooms understand transition risk better than physical risk; and everyone assumes insurance or government will eventually solve the problem. Companies have assessed their exposure. Companies have disclosed it in regulatory filings. Companies have allocated almost no capital to address it. Soon, this inaction will carry a price.

The Incentive Structure Creaking Under Climate Chaos

The private-sector abdication is comprehensive and structural. Infrastructure investments in adaptation—water systems, transportation networks, coastal defences—remain largely in the public domain, where they languish for lack of fiscal capacity. Insurance companies, theoretically risk management specialists, are instead retreating from high-risk markets, raising premiums at rates that make ‘self-insurance’ through personal capital expenditure suddenly rational.

Why? Start with the incentive structure. The stakeholders who measure climate risk—the chief risk officer, the sustainability team—do not typically control the capital budget. A conflict exists with the person who controls the capital budget—typically the CFO, and the lack of long-term data and models to make data-driven investments in resilience. Meanwhile, everyone has an incentive to assume that someone else will solve the problem: the government, insurers, future management teams, or the free market, eventually recognising adaptation opportunities. It’s the free-rider problem at its worst.

This is magical thinking. When a one-in-50-year flood arrives every five years, insurance becomes unaffordable. Governments, especially in developing nations, lack the fiscal capacity to bail out private firms. And markets, once they realise adaptation is underpriced, move with the blunt force of repricing.

Early examples are emerging. Utilities like NextEra Energy’s subsidiary FPL have invested over $6.8 billion in grid hardening since 2020. The operational payoff is now empirically proven: during the 2024 hurricane season, their underground power lines performed 5 to 14 times better than overhead counterparts, while hardened main power lines showed zero failures from wind impact during Hurricanes Helene and Milton. Siemens has committed €500 million to the elevation of manufacturing facilities in flood-prone European regions, reducing climate-related downtime by 15 to 20%. HSBC pioneered adaptation-linked finance, issuing bonds where interest rates adjust based on physical risk management progress.

These are outliers. Energy majors like ExxonMobil acknowledge climate risks in 10-K filings while channelling capital to oil and gas exploration. Automotive manufacturers discuss supply-chain resilience whilst operating supply chains largely unchanged for decades. Technology and finance firms, sitting atop vast cash reserves, have largely opted out of meaningful adaptation strategies—a curious blind spot for sectors claiming climate leadership.

The Resilience Regulatory Reckoning

Corporate boards are running out of time to treat adaptation as a medium-term problem. The European Union's Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, which took effect for large companies in fiscal year 2024, mandates explicit disclosure of climate transition plans, including adaptation strategies. The International Sustainability Standards Board's disclosure standards now also require climate-related financial risk analysis. IFRS Sustainability Standards are converging on the same principle: climate risk is not a sustainability issue; it is a balance-sheet issue.

As transparency improves, the absence of adaptation capex becomes indefensible. Companies that acknowledge physical risks whilst allocating zero capital to resilience are signalling one of two things: either they do not genuinely believe their own risk disclosures, or they are betting that insurance and government will cover the damage. Both messages should be red flags for investors.

This is where repricing begins. Expect to see valuation discounts for non-aligned firms accelerate in the medium-term. Expect borrowing costs to spike for companies with material climate exposures, but zero disclosed adaptation strategies. Expect insurance availability to contract further in high-risk geographies, forcing firms to internalise costs through capex or face operational disruption.

The alternative is straightforward. Firms allocating meaningful capital (e.g. 5-7% of capex) to resilience-building—supply-chain diversification, facility elevation, distributed operations, pre-positioned emergency reserves—will be positioned as prudent managers. Initial evidence suggests such investments generate 10 to 20% risk-adjusted returns by avoiding downtime and asset losses. When climate impacts inevitably arrive, the winners will be those who invested in redundancy when it seemed wasteful.

When Delay and Inaction Become Untenable

The corporate adaptation paradox is not permanent. The gap between acknowledged risk and capital allocation will close as impacts mount. The only question is whether it closes proactively—through strategic capex allocation by forward-thinking boards—or reactively, through the blunt force of regulation, insurance withdrawal, and risk repricing by capital markets.

For most firms, the window for change is still open. But it is narrowing fast. The confessions are on record. The risks are being quantified. What remains is execution. And execution, in an era of accelerating climate impacts and tightening financial markets, will no longer be optional.

Know someone interested in adapting to a warmer world? Share Liveable with someone who should be in the know.

Or copy and paste this link to share with others: https://research.liveable.world/subscribe